It’s been a year of calls to action. Naomi Klein tackled climate change,

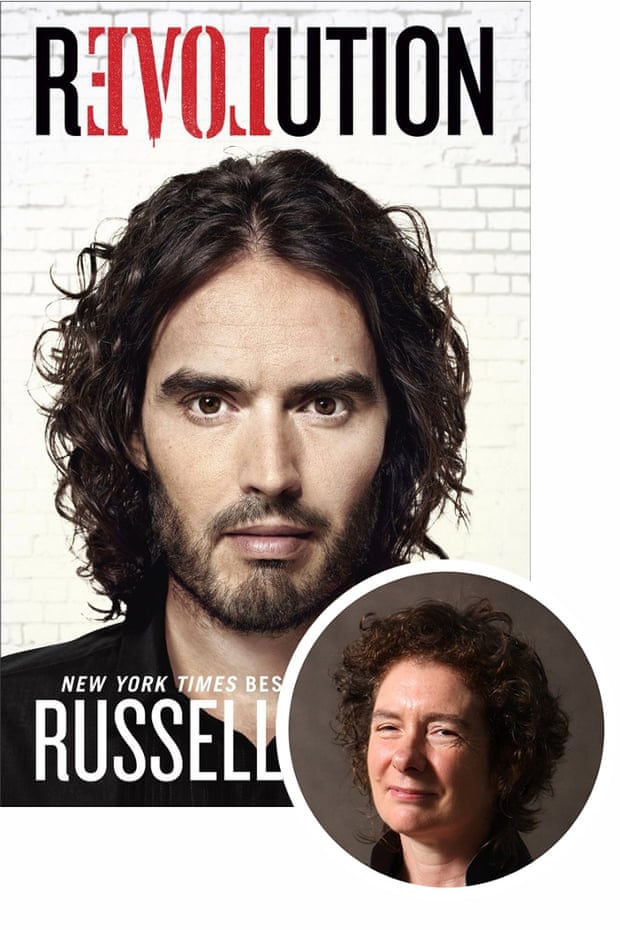

Owen Jones got to grips with class politics, and Russell Brand preached

revolution. Writers from Hilary Mantel to Lena Dunham recommend the

titles that leaped out at them this year.

Margaret Atwood

This Changes Everything by Naomi Klein

Julian Barnes

You’ll Enjoy It When You Get There by Elizabeth Taylor

Mariusz Szczygiel’s Gottland

(Melville House) is one of those delightfully unclassifiable books: a

Polish journalist’s informal history of 20th-century Czechoslovakia.

Like a non-fictional Bohumil Hrabal,

Szczygiel is strange and funny, constantly off at jaunty tangents. He

begins with 40 pages about the Bata shoe factory and ends with a

brilliantly worked double narrative about a female burns doctor who

translates Dick Francis in her spare time. And it’s all true, too.

Mariusz Szczygiel’s Gottland

(Melville House) is one of those delightfully unclassifiable books: a

Polish journalist’s informal history of 20th-century Czechoslovakia.

Like a non-fictional Bohumil Hrabal,

Szczygiel is strange and funny, constantly off at jaunty tangents. He

begins with 40 pages about the Bata shoe factory and ends with a

brilliantly worked double narrative about a female burns doctor who

translates Dick Francis in her spare time. And it’s all true, too.Margaret Drabble’s selection of Elizabeth Taylor’s short stories, You’ll Enjoy It When You Get There (NYRB), shows a novelist entirely at ease with the shorter form: seemingly quiet and suburban tales that enclose rage and despair; Taylor is also very good on pubs and drinking.

Bob Mankoff’s How About Never – Is Never Good for You? (Henry Holt) is a charming autobiography that answers one of the minor yet gripping questions of magazine publishing: who gets to choose the cartoons in the New Yorker (he does), what’s it like to submit one (nerve-shredding), and what percentage gets chosen (infinitesimal). A cheering book, nonetheless.

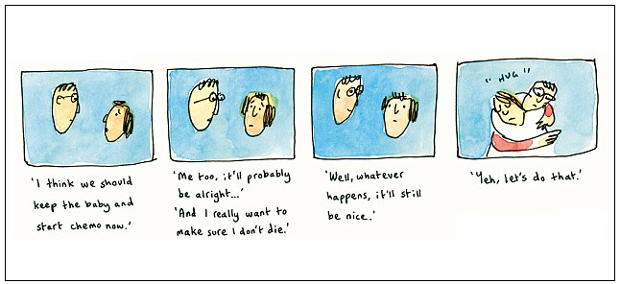

Laura Bates

Probably Nothing by Matilda Tristram

The other standout books of the year have been two wonderful but completely different poetry collections. Outside Looking On (Influx) by Chimene Suleyman presents startlingly perceptive snapshots of human experience, delving powerfully into themes that range from big-city loneliness and longing, to prejudice and love.

And When I Grow Up I Want to Be Mary Beard (Burning Eye), by student slam-poet sensation Megan Beech, is a vibrant and exciting exploration of gender inequality, modern feminism and what it means to be a young woman in the 21st century.

Mary Beard

The Smile Revolution by Colin Jones

For the future, trips out in Cambridge will be enhanced by Simon Bradley’s revision of the Pevsner (Buildings of England) Guide to Cambridgeshire (Yale). It was much in need of updating and Bradley manages it expertly, without destroying the sparky style of the original.

William Boyd

Letter to Vera, edited and translated by Olga Voronina and Brian Boyd

Sailing the Forest (Picador) by Robin Robertson is a wonderfully generous selected poems. Great precision of language, limpid observation and a rare ability to make the narrative of the poems resonate evocatively. A ripple-effect that is remarkably profound.

Craig Brown

The Interestings by Meg Wolitzer

A fan once came up to Bob Dylan and said: “You don’t know who I am, but I know who you are.” To which Dylan replied: “Let’s keep it that way.” The Dylanologists (Atria) by David Kinney is a razor-sharp study of the crackpot world of the obsessive fan, by turns very funny and slightly scary. Dylan’s extreme standoffishness has only served to fuel his fans’ need to get closer to him; the obscurity of his lyrics increases his fans’ need to interpret them. The great man seems to love and loathe it all, in roughly equal measures.

Shami Chakrabarti

Eleanor Marx: A Life by Rachel Holmes

The Establishment (and How They Get Away with It) by Owen Jones (Allen Lane): at a time when politicians aspire to be pop stars and vice versa, it is refreshing that a genuine political writer and thinker can achieve such popular appeal. Whether you agree or disagree with the Jones analysis, I challenge you not to be captivated by the authenticity of his voice.

Josh Cohen

The Iceberg by Marion Coutts

Leaving the Sea (Granta), Ben Marcus’s wonderfully various short-story collection, left me hungrily awaiting his next offering. And The Infatuations (Penguin) confirmed Javier Marías for me as among the best writers alive.

Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett

Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill

Spoiled Brats by Simon Rich (Serpent’s Tail) is a collection of offbeat, surreal short stories, some of which appeared in the New Yorker. “Sell Out”, the story of a simple man who falls into a vat of pickles and awakes in modern-day Brooklyn, is a very funny skewering of hipsterdom.

The Empathy Exams by Leslie Jamison (Granta). To my mind, there aren’t enough British essayists, which is why, as a fan of Joan Didion and Nora Ephron, I turn so often to American writers. As the title suggests, this collection examines empathy and what it means to feel pain, and covers topics ranging from Morgellons to Nicaragua to a job Jamison once had as a medical actor for trainee doctors, and each essay is illuminating, stylish and a pleasure to read.

Lena Dunham

Women by Chloe Caldwell

Chloe Caldwell’s Women (Hobart) is another deceptively teensy book. This is the tragicomic tale of the author’s doomed relationship with an older woman and it perfectly captures the way good sex can make us throw anything under the bus – even our identities.

Mira Gonzalez’s I’ll Never Be Beautiful Enough to Make Us Beautiful Together (Sorry House) brings experimental poetry into the internet age with dark, distinctly female riffs on ambition, depression and love.

John Gray

Mr Weston’s Good Wine by TF Powys

Now out in a new edition published by Vintage, Mr Weston’s Good Wine

by TF Powys is one of the classics of English literature – and one of

the strangest and most delightful books I’ve ever read. The story and

the style are unfathomably simple. Accompanied by an assistant called

Gabriel, a woolly-haired wine-seller drives into a small Dorset town

called Folly Down. Time stops, and the sign on the battered van appears

in the sky. Some in the town drink the light wine Mr Weston is selling,

others the dark. Realising that the town is his own creation, the

wine-seller longs to drink the dark wine himself. If you want to know

how Mr Weston’s visit ends, you’ll have to read the book.

Now out in a new edition published by Vintage, Mr Weston’s Good Wine

by TF Powys is one of the classics of English literature – and one of

the strangest and most delightful books I’ve ever read. The story and

the style are unfathomably simple. Accompanied by an assistant called

Gabriel, a woolly-haired wine-seller drives into a small Dorset town

called Folly Down. Time stops, and the sign on the battered van appears

in the sky. Some in the town drink the light wine Mr Weston is selling,

others the dark. Realising that the town is his own creation, the

wine-seller longs to drink the dark wine himself. If you want to know

how Mr Weston’s visit ends, you’ll have to read the book.Translated into English for the first time by Siân Reynolds, The Mahe Circle (Penguin Classics) is one of Georges Simenon’s most powerful roman durs – the non-Maigret novels in which ordinary lives are suddenly, and at times seemingly inexplicably, unsettled and irrevocably changed. Written in Simenon’s spare signature style, it’s unputdownably gripping.

Anthony Powell’s What’s Become of Waring first appeared in 1939, and has been republished this year by the University of Chicago Press. Recognisably the work of the author of A Dance to the Music of Time, it’s lighter and funnier than the later 12-volume cycle. But in some ways it’s also more cruel – a tale of literary charlatanry, set in the decayed world of interwar London publishing. I found it irresistible, and wish it had been twice as long.

Owen Jones

Austerity Bites by Mary O’Hara

Arun Kundnani’s The Muslims Are Coming is a fantastic counterblast to the rise of Islamophobia.

Philip Hensher

We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves by Karen Joy Fowler

James Hamilton’s A Strange Business (Atlantic) is a brilliantly engaging account of the most interesting of all subjects: how artists make their money, in this case in 19th-century England. The book was published just in time to cast a curious light over the Tate’s splendid late-Turner show.

And the novel I liked best was Karen Joy Fowler’s We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves (Serpent’s Tail).

Naomi Klein

The Establishment by Owen Jones

In non-fiction, Glenn Greenwald’s No Place to Hide (Hamish Hamilton) has far more staying power than the ripped-from-his-own-headlines topic might suggest, laying out a powerful and persuasive case for the duty to defend our fast-disappearing privacy.

I’ll never look at UK class politics in the same way after Owen Jones’s bracing and principled The Establishment: How They Get Away With It.

The best kids’ book I read to my two-year-old son is the beautiful and playful Julia, Child by Kyo Maclear (Tundra).

Mark Lawson

Amnesia by Peter Carey

It’s unusual on these occasions to recommend books that are often almost unreadably revolting; but, if we have to try to understand what Jimmy Savile and Cyril Smith did and why the British establishment let them, there are unlikely to be more thorough and troubling accounts than In Plain Sight: The Life and Lies of Jimmy Savile by Dan Davies (Quercus) and Smile for the Camera: The Double Life of Cyril Smith by Simon Danczuk and Matthew Baker (Biteback).

Linking the Assange and Snowden affairs with the UK crown’s coup against the Australian government in 1975, Peter Carey’s Amnesia (Faber) is a completely original political novel.

But the work to which I kept returning this year was KP: The Autobiography (Sphere), Kevin Pietersen’s report from the England cricket changing room: an eye-popping account of malicious secret dossiers, snitching team-mates and the search for a scapegoat to protect mediocre managers – all happening within one of the flagship clients of the Department for Culture Media and Sport.

Penelope Lively

On Silbury Hill by Adam Thorpe

Adam Thorpe’s On Silbury Hill

(Little Toller) is about that mysterious Wiltshire mound – archaeology,

history, landscape – but with an undertow of memoir: brilliant.

Adam Thorpe’s On Silbury Hill

(Little Toller) is about that mysterious Wiltshire mound – archaeology,

history, landscape – but with an undertow of memoir: brilliant.Margaret Forster’s My Life in Houses (Chatto & Windus) is such a clever idea. It’s a memoir sited in bricks and mortar, from childhood home to student lodging to marital home, to holiday cottage in Cumbria – social and personal history spliced together.

My roots are in West Somerset, so the new Somerset: South and West edition of Pevsner’s Buildings of England (Yale) is warmly welcome. The old one, by Pevsner alone, was somewhat skimpy; Julian Orbach’s revisit is huge, reflecting the architectural riches of the area, and there is wealth within – informative and scholarly text, handsome photographs.

Robert Macfarlane

A Book of Death and Fish by Ian Stephen

The poems of Ancient Sunlight (Enitharmon), by the poet, translator and editor Stephen Watts, moved and fascinated me, especially the long poem “The Birds of East London”, and Watts’s elegy for his friend and walking companion, WG Sebald.

Lastly, Philip Marsden’s superb “search for the spirit of place”, Rising Ground (Granta), which takes Cornwall as its focal terrain, and the idea of sacred landscape as its subject.

Hilary Mantel

Outline by Rachel Cusk

Winter bouquets should be offered to the clever and stylish Rachel Cusk: her novel Outline (Faber) is smoothly accomplished, and fascinating both on the surface and in its depths.

Eimear McBride

The Notebook by Ágota Kristóf

Martin Dyar’s poetry collection Maiden Names (Arlen House) is both poignant and incisive, while Nigel McDowell’s children’s novel The Black North (Hot Key) is a great read and a cunning reworking of Irish history and lore into fantasy.

But the unstoppable CB Editions’ reissue of Ágota Kristóf’s The Notebook is the book I have not been able to stop thinking about all year.

Pankaj Mishra

A Voice Still Heard: Selected Essays by Irving Howe

The Collected Poems (1969-2014) of Arvind Krishna Mehrotra (Penguin), superbly introduced by Amit Chaudhuri, represent an older kind of literary achievement: cumulative, unshowy and consistently brilliant.

The Collected Poems (1969-2014) of Arvind Krishna Mehrotra (Penguin), superbly introduced by Amit Chaudhuri, represent an older kind of literary achievement: cumulative, unshowy and consistently brilliant.Irving Howe’s A Voice Still Heard: Selected Essays (Yale) reminds us of the void this great critic left in anglophone commentary – one that David Bromwich has been filling in the last decade with the searing pieces collected in Moral Imagination (Princeton).

As mendacious nationalisms pollute the air from Japan to Hungary, Ranjit Hoskote and Ilija Trojanow’s Confluences: Forgotten Histories from East and West (Yoda) points to an unimpeachable history of culture and society.

In his angrily subversive but always funny comic novel Bumf (Jonathan Cape), the graphic writer Joe Sacco has found a perfect target in the machinery of politics and mass manipulation.

Michael Morpurgo

Quentin Blake by Joanna Carey

Quentin Blake by Joanna Carey

(The House of Illustration): in a way, this beautiful book is a

celebration of the opening of The House of Illustration, a project

instigated by the great and beloved Quentin Blake. Carey has composed a

fond appreciation of the artist and his work, which is, of course,

wonderfully illustrated.

Quentin Blake by Joanna Carey

(The House of Illustration): in a way, this beautiful book is a

celebration of the opening of The House of Illustration, a project

instigated by the great and beloved Quentin Blake. Carey has composed a

fond appreciation of the artist and his work, which is, of course,

wonderfully illustrated.A Ted Hughes Bestiary selected by Alice Oswald (Faber): a collection of Hughes’s poetry of animals, wild and imagined, selected by Oswald is very much the inheritor of his mantle and understands Hughes and his world as well as anyone. Hughes’s poems are not all tooth and claw, as often imagined, but, rather, he opens our senses to the natural world as no one else can.

Blake Morrison

I Refuse by Per Petterson

The best biography I’ve read in 2014 is Adam Begley’s Updike (HarperCollins), an admiring but not uncritical portrait of a novelist who was merciless in drawing on his own experiences, sexual and otherwise.

And I’m enjoying A Modern Don Juan, edited by Andy Croft and NS Thompson (Five Leaves), in which 15 contemporary poets lend fresh interest to Byron’s cantos, thanks to some ingenious modern rhymes (sequined cap / Gangsta rap, Che poster / pop-up toaster, Minerva’s Owl / Simon Cowell).

Andrew Motion

Paper Aeroplane by Simon Armitage

The poet Rosemary Tonks

made her name in the 60s and 70s, then withdrew from public sight and

published nothing in the later part of her life. Following her recent

death, Neil Astley has collected and introduced her work in Bedouin of the London Evening (Bloodaxe).

It’s a highly original collection, mingling savage realism with a

surreal fancy, and it restores an essential voice of late-20th-century

British poetry to its rightful place.

The poet Rosemary Tonks

made her name in the 60s and 70s, then withdrew from public sight and

published nothing in the later part of her life. Following her recent

death, Neil Astley has collected and introduced her work in Bedouin of the London Evening (Bloodaxe).

It’s a highly original collection, mingling savage realism with a

surreal fancy, and it restores an essential voice of late-20th-century

British poetry to its rightful place.And among our contemporaries: one mid-career gathering of great distinction – Simon Armitage’s new and selected poems Paper Aeroplane (Faber), and two outstandingly good pamphlets from recent arrivals: Sam Riviere’s Standard Twin Fantasy (Egg Box) and Declan Ryan’s selection for Faber New Poets 12 (Faber).

David Nicholls

Bark by Lorrie Moore

Ian Rankin

The Zone of Interest by Martin Amis

I Can See in the Dark

by Karin Fossum (Vintage) is an off-kilter crime story about a

disturbed care worker and his murderous life. Unsettling and scarily

well written. The Zone of Interest

(Jonathan Cape) is Martin Amis’s best novel in years, a grim yet

satire-flecked investigation of the Nazi death camps. Van Morrison’s Lit Up Inside (Faber) collects many of the great man’s favourite lyrics, and includes a foreword by a long-time fan.

I Can See in the Dark

by Karin Fossum (Vintage) is an off-kilter crime story about a

disturbed care worker and his murderous life. Unsettling and scarily

well written. The Zone of Interest

(Jonathan Cape) is Martin Amis’s best novel in years, a grim yet

satire-flecked investigation of the Nazi death camps. Van Morrison’s Lit Up Inside (Faber) collects many of the great man’s favourite lyrics, and includes a foreword by a long-time fan.Ruth Rendell

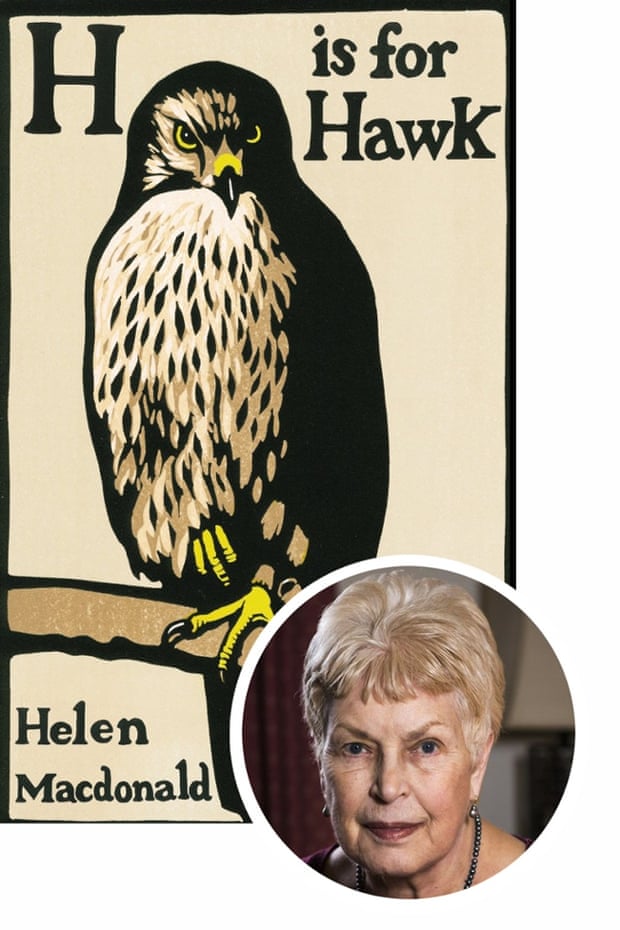

H Is for Hawk by Helen Macdonald

Sarah Waters’ The Paying Guests (Virago): the only fault I have to find with Waters is that she writes too seldom. I expected to take this novel, all 564 pages of it, at a leisurely pace. But I raced through it, breathing fast and when I had finished had to reread parts of the wonderful early chapters. I don’t like historical novels but this is the exception. I shall let a few months go by and then read it all over again with, I’m sure, undiminished pleasure.

Kamila Shamsie

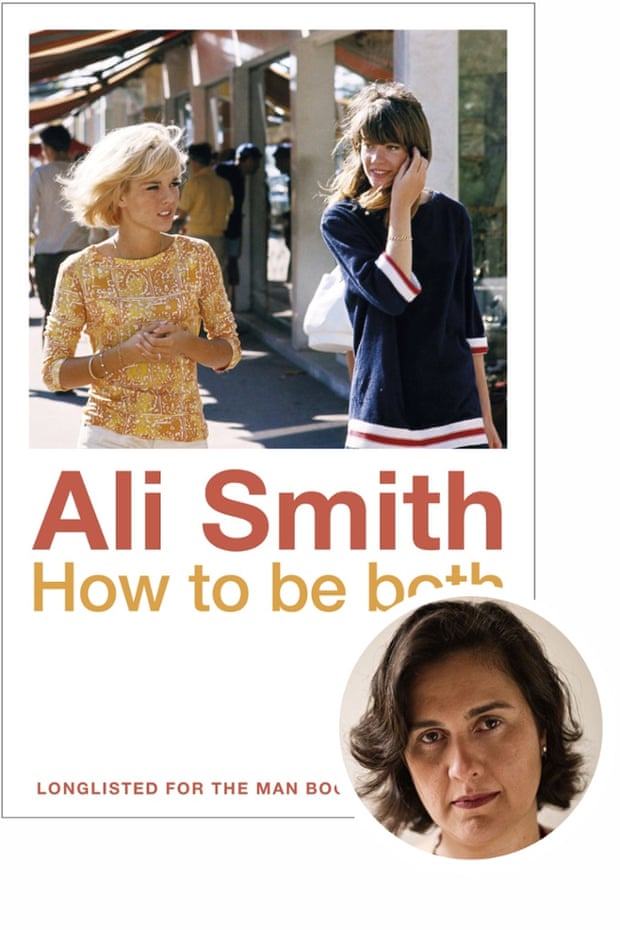

How to Be Both by Ali Smith

Jeanette Winterson

Revolution by Russell Brand

And to stop myself going mad, add the sublime Don Paterson’s Smith (Picador), his eccentric, beautiful zen guide to the poetry of Michael Donaghy.

• Compiled by Laura Kemp. To order any of the books of the year, call Guardian book service on 0330 333 6846 or go to guardianbookshop.co.uk.

• This article was amended on 29 November 2014 to remove a statement that Lit Up includes a foreword by poet David Meltzer, which referred to the book’s US edition. The UK edition has a foreword by Ian Rankin.

sursa: theguardian.com